So Long Stare Decisis

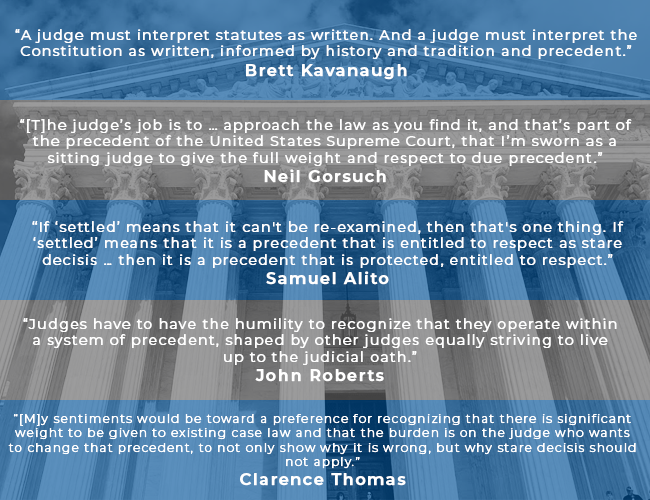

“I will respect precedent!”

–members of the conservative majority on the Supreme Court whispered quietly into the wind as they raced back to the partisan enclaves they crawled out of…)

The promise to respect and follow precedent – made by so many of our nation’s nominees to the federal bench – has turned out to be a flexible vow for many. Strikingly, the additions of Justices Gorsuch and Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court seem to have made the Roberts Court more determined than ever to do away with the pesky little hurdle responsible for keeping vital public protections in place: precedent. The influence of these new justices has only amplified the tendency of the Court’s longstanding precedent skeptic, Clarence Thomas, to attack precedents he dislikes.

Whether it’s overturning 40-plus years of precedent related to public unions, or the growing threats to overturn 40-plus years of abortion rights under Roe v. Wade, the current Supreme Court has apparently decided that precedent is, in fact, malleable when it needs to fit the justices’ ideological preferences.

This concerning trend, which was publicly highlighted during the 2018 Supreme Court term, is especially troubling as we look toward the future SCOTUS term and the wave of important, precedent-reliant issues coming before the Court to resolve. These include whether draconian abortion bans are unconstitutional and if Roe v. Wade should be overturned; whether the Affordable Care Act is constitutional; whether localities can impose gun control measures regarding transporting weapons; and whether major environmental and Native American land rights should be overturned.

The justices’ respect – professed vs. actual – for precedent could have enormous impacts on the rights we care most deeply about and fight to protect.

Precedent, and the accompanying legal doctrine of “stare decisis,” (which is a trying-too-hard-to-be fancy, Latin-turned-legal term meaning: “to stand by decided cases; to uphold precedents; to maintain former adjudications”) is a longstanding principle in United States law. The basic idea is that any legal argument a lawyer makes, and a court upholds, should mesh with established law and conform to prior judicial decisions on that law; generally, the older the precedent, the more the prior judicial holding tends to be respected and followed.

There seems to be a growing trend amongst the conservative majority of the Roberts Court: To get confirmed, ardently support the idea of upholding precedent; then, to achieve what the conservative apparatus who put you on the bench wants, bulldoze any precedent you don’t like.

This practice isn’t terribly new for the Roberts Court: Prior to this term, the Court overturned decades of precedent in a variety of landmark cases, including: Citizens United v. F.E.C. (2010) (overruling two key campaign finance precedents: Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce (1990) and McConnell v. Federal Election Commission (2003)); Leegin Creative Leather Products v. PSKS, Inc. (2007) (overturning a 1911 anti-trust precedent in Dr. Miles Medical Co. v. John D. Park & Sons Co.); and Montejo v. Louisiana (2009) (overturning a 1986 precedent regarding right to counsel established in Michigan v. Jackson).

But the Roberts Court history of overturning precedent that doesn’t comport with its ideological agenda reached new heights during the 2018 SCOTUS term. For example, the Court overturned 40-plus years of precedent protecting public section unions in Janus v. AFSCME. The decision overruled Abood v. Detroit Board of Education which for decades had allowed public sector unions to collect fees from public employees for the purposes of collective bargaining and enforcing fair, safe conditions in the workplace. As Justice Kagan explained in her powerful dissent, “Abood is not just any precedent: It is embedded in the law.” Her dissent highlighted the sinister underpinnings of the majority’s opinion in Janus: “The majority overthrows a decision entrenched in this Nation’s law— and in its economic life—for over 40 years.” Kagan also powerfully highlighted how the “majority overruled Abood for no exceptional or special reason, but because it never liked the decision. It has overruled Abood because it wanted to.”

Then came the 2019 Supreme Court session, when Justice Brett Kavanaugh joined the bench after a confirmation process riddled with controversy, sexual assault claims, and threats of future political reprisal. Once again, the conservative majority freely thumbed their noses at precedent when it didn’t fit their ideological agendas. For example, Justice Thomas wrote the majority opinion in Franchise Tax Bd. of Cal. v. Hyatt to overrule 40 years of precedent regarding when a state can be sued in another state. In his dissent, Justice Breyer argued that it is “dangerous to overrule a decision only because five Members of a later Court come to agree with earlier dissenters on a difficult legal question” and prophetically suggested how the “decision can only cause one to wonder which cases the Court will overrule next.”

And sure enough, a little over one month later in Knick v. Township of Scott, Pennsylvania, the majority overruled 34 years of precedent to hold that litigants who allege local takings of their property by the state do not need to first bring their claim in a state court. Justice Kagan, once again assuming the role of precedent-bodyguard, powerfully dissented from the majority’s trampling of decades-old precedent: “The majority today holds, in conflict with precedent after precedent, that a government violates the Constitution whenever it takes property without advance compensation—no matter how good its commitment to pay… it transgresses all usual principles of stare decisis.”

While the newest additions to the Court have shown a strong appetite for overturning precedent, as we’ve mentioned they are preceded – and surpassed – in their zeal for wrecking precedent by their senior colleague, Justice Thomas. In fact, Justice Thomas has spent his time on the Supreme Court opposing the very premise of following precedent. In a concurrence in Gamble v. United States, Thomas clearly professed his view on precedent: “When faced with a demonstrably erroneous precedent, my rule is simple: We should not follow it.” In his history of combating precedents that he views as “demonstrably erroneous,” Justice Thomas has argued against respecting decades of precedent, including arguing in Flowers v. Mississippi that the Batson decision prohibiting striking jurors from serving on a jury based on race was wrongly decided; questioning the application of the holding in Mapp v. Ohio (holding “that all evidence obtained by searches and seizures in violation of the Constitution is, by that same authority, inadmissible in a state court”) to federal courts; and arguing that the Voting Rights Act doesn’t apply to redistricting.

Indeed, the 2019 SCOTUS session revealed an unusually prolific version of Justice Thomas. In one of his most revealing writings, he dissented from the Court’s decision not to hear an appeal for the Alabama abortion ban case. In his dissent, Thomas exposed his deep desire to do away with decades of abortion rights precedent to outlaw abortion. He wrote how the case the Court declined to hear “serves as a stark reminder that our abortion jurisprudence has spiraled out of control … Although this case does not present the opportunity to address our demonstrably erroneous ‘undue burden’ standard, we cannot continue blinking the reality of what this Court has wrought.” In other words, Thomas would like us to ignore long-standing precedent because he and his conservative pals have fought for decades to strip constitutional rights, equality, and power away from women.

Thomas also set aside time in the 2019 SCOTUS session to set a new, alarming precedent of his own: calling for overturning 50-plus years of precedent twice within two weeks. The first of the two occurred in February 2019, when Thomas called for the Supreme Court to overturn New York Times v. Sullivan (a 55-year-old precedent that protects freedom of speech and freedom of the press by setting strict standards for public official to win libel suits). Less than two weeks later, Thomas, along with Justice Gorsuch, dissented in Garza v. Idaho (arguing to overturn 56 years of precedent relating to a criminal defendant’s right to counsel, established in Gideon v. Wainwright). Thomas challenged not only the right to effective counsel in criminal cases, but also the right to counsel at all.

As the most recent term has amply demonstrated, the new conservative majority’s professed respect for adhering to precedent holds no water. All that matters is how Thomas and the conservative majority on the Robert’s Court achieve the conservative agenda that the movement has failed to implement legislatively. In response, advocates must be ever- diligent in monitoring the Court and fighting to protect the rights that are currently in jeopardy. We have every reason to worry that the Court’s five conservatives will continue to disregard decades of precedent to benefit themselves and their right-wing allies.